This op is written from a sommelier’s perspective. I know a lot of them because I was a sommelier who worked in restaurants for over 28 years, and am currently affiliated SOMM Journal.

—Randy Caparoso

This I can say about sommeliers: Most of them hate Zinfandel.

Putting it more gently: Of all the popular varietal categories, Zinfandel is the one that sommeliers have the hardest time drumming up enthusiasm for. Sure, the cultivar has historic connotations as “America’s” grape, even though we now know it originated in Croatia. But we still consider it historical because, in the 1800s, Californians found it to be the easiest grape to grow in the state’s climatic conditions—and it produced (the most consistently) good wine.

That is a terroir-based relationship, isn’t it? Aren’t sommeliers into terroir?

Somewhere between the 1970s and 1980s, however, the varietal became a caricature of itself. “Big” styles made from ultra-ripe grapes became the most popular. “No wimpy wine” became a mantra, and the variety’s character was defined as “jammy.” If grape sugars were too high to get wines lower than 17% ABV, no problem. Winemakers simply added water, adjusted acidity, and tacked on a ton of oak flavor—preferably American oak, which adds sweetly vanillin, char, dill, and often a furniture polish-like quality. That was the formula for “America’s wine.”

Then there’s the common practice of blending Petite Sirah, anywhere from 10 to over 20 percent for most commercial Zinfandels. The additional grape adds color, tannin, blacker fruit and spice qualities, but has as much to do with uplifting pure Zinfandel as those American oak barrels. They are both embellishments, nothing more. But somewhere along the line they became expected along with those jammy, over-ripe characteristics.

Much Zinfandel is still made this way. The good news is that more and more of them aren’t. Just over ten years ago, for instance, Turley Wine Cellars—once the poster child for huge, jammy Zinfandels—began taking control of their own vineyard sources. Once they were able to grow grapes with more ideal sugar/acid levels, resulting vineyard-designate wines became fresher, more floral (in actuality, pure Zinfandel is more flowery than jammy), and delineated in terms of vineyard-related qualities.

Turley, like other Zinfandel producers such as the iconic Ridge Vineyards, still employs a little new oak (20 to 25 percent) in its cooperage program, but at least their Zinfandels now taste like the actual fruit and not something pumped up by vinous equivalents to steroids. There are now numerous other handcrafted examples, brands that age strictly in neutral wood, pick grapes earlier, stick to native yeast fermentation (as Turley and Ridge have always done), and retain a more natural acid-driven edginess.

Progress.

Zinfandels need no longer be fat, sweetly fruited and oaky—the things sommeliers hate most. While many brands popular with consumers are still made that way, there are now lots of choices that are the opposite: Zinfandels is zesty, balanced and food-versatile. (In my experience as a restaurateur, Zinfandel can be even more food-versatile than most Pinot Noirs.)

Napa and Sonoma-grown Zinfandels are still the sturdiest in tannin and can be quite big and ripe; but these qualities are dictated by their hillside or clay soil origins, not winemaker decisions or brand styles. You can now buy single-vineyard bottlings grown in Lodi or Contra Costa County that are soft yet zesty, red fruited and earthy—qualities that are byproducts of sandy soils. Paso Robles Zinfandels tend to be very ripe but minerally, with surprising acidity—reflections of their own unique terroir, often couched on high-pH, calcareous slopes.

My point is, many of the contemporary style Zinfandels crafted more seriously (ie: as an expression of place or artistry, and not a stock image of its former reputation) are more than worthy of the attention of the most persnickety sommeliers. The big challenge now, of course, is to convince them.

_______________________________________________________________________

Expert Editorial

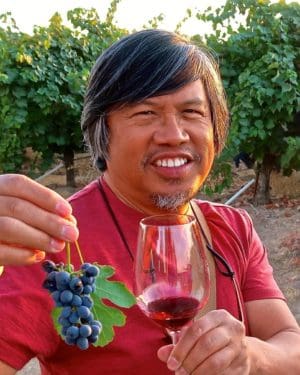

Randy Caparoso is a full-time wine journalist/photographer living in Lodi, California. In a prior incarnation, he was a multi-award winning restaurateur, starting as a sommelier in Honolulu (1978 through 1988), and then as Founding Partner/VP/Corporate Wine Director of the James Beard Award winning Roy’s family of restaurants (1988-2001), opening 28 locations from Hawaii to New York. While with Roy’s, he was named Santé’s first Wine & Spirits Professional of the Year (1998) and Restaurant Wine’s Wine Marketer of the Year (1992 and 1998). Between 2001 and 2006, he operated his own Caparoso Wines label as a wine producer. For over 20 years, he also bylined a biweekly wine column for his hometown newspaper, The Honolulu Advertiser (1981-2002). He currently puts bread (and wine) on the table as Editor-at-Large and the Bottom Line columnist for The SOMM Journal (founded in 2007 as Sommelier Journal), and freelance blogger and social media director for Lodi Winegrape Commission (lodiwine.com). You may contact him at randycaparoso@earthlink.net.