Hands off those vines, hands off those wines—what comes naturally should be respected

—Randy Caparoso

I love natural style wines. In fact, I’m partial to them, and for good reason: Because wines made in this style give you the highest percentage chance of experiencing a wine that expresses the vineyard where it’s grown, or the appellation of its origin.

It’s not so much a matter of personal taste, it’s more about how I originally came into this industry when training to become a full-time sommelier, back in the late 1970s. In those days we learned, for instance, that Lafite is Lafite, which is different from Margaux, Haut-Brion, or Cheval Blanc. Why? Because they are different vineyards, reflecting completely different terroirs—naturally. This was as basic as A, B, C, and still is.

For the longest time, however, I could never understand why American wines couldn’t be understood, or appreciated, in the same way. It seems American wines have historically been made to fulfill expectations such as “varietal character,” or to reinforce sensory qualities associated with specific brands. That’s how many premium producers chalk up the “scores,” which drive wine sales.

Yet, in the US, vineyard or regional expressions, a sense of place, terroir—whatever you want to call it—typically takes a back seat.

Andrea Cairone, Unsplash

But American wines don’t have to be that way. In fact, more and more of them aren’t. The more a winery is willing dispense with machinations meant to conform to varietal standards or brand style, or the more a winemaker is able to restrain personal compulsions to do this or that to a wine, then the more likely a wine is able to attain sensory qualities that express their origins—naturally.

This, if anything, is the essence of the so-called “natural” style.

Many of the consumers who are now looking for “natural” wines, of course, are not necessarily longtime wine lovers with copious amounts of wine knowledge. There is a lot of evidence that this growing preference is generational—harbored by the simple fact that new generations do not necessarily have the same taste as their parents or grandparents in much of anything, including wine.

A lot of these consumers have obviously had enough of what might be considered “conventional” wines—domestically produced products that continue to dominate America’s commercial market. Like it or not, these consumers find most of these wines to be either boring, unfulfilling or, simply, unpleasant. So, they look for alternatives—wines that speak to their taste and, often, also fit in with their values as consumers. For many of them, that alternative is “natural.”

Put it this way: To you, it may make more sense that a Cabernet Sauvignon should be intense and powerful, a Pinot Noir soft and sumptuous, and a Chardonnay rich and layered. But there are now many wine lovers who prefer red wines that are lean, sharp, earthy or herby, and white wines that are light, stony, decidedly un-fruity, even “un-varietal.”

The positive thing about the interest in natural wines is that they do, indeed, push conventions. On the negative side, we see continuous criticism of producers and companies marketing natural styles because it is felt that their sales pitches suggest that wines not made this way are somehow inferior. But that’s sales. No matter what you pitch—be it native yeast over inoculated fermentations, neutral over new French oak, amphorae over stainless steel finished wines, or even simply pushing your specific AVA— this does not automatically mean someone is saying that the opposite of said winemaking choice or style is bad. This is just how wines are sold.

The other common criticism is that people should not be allowed to use the term “natural” because it’s not clearly defined and is unregulated. Terms like “Reserve” and “Old Vine” are also ill-defined and unregulated, but who wants to give up the freedom to use those designations as they please? As it is, there are plenty enough things on wine labels that you do not have any freedom to fudge on. A while back, the feds in their great benevolence decided to tackle the term “organic,” and look what that got us—the absurd law that only unsulfured wines may be labeled “organic.”

Notwithstanding France’s 2020 enactment of official guidelines for Vin Méthode Nature wines, the stupidest thing we can do is beg our own government for more regulations. For now, we’re better off letting people call their wines “natural.”

I only had two mentors in the early part of my career, André Tchelistcheff and Kermit Lynch. While he is now retired, Lynch’s role as an importer of terroir-focused wines has had a huge impact on the way Americans look at wine. While being “natural” was absolutely never a defining objective by which Lynch made his selections, it’s no coincidence that most of the wines in the Kermit Lynch Wine Imports portfolio tend to meet this criterion. He is now considered The Godfather of this movement.

What I find more interesting is Tchelistcheff, who you can say made wine for, or consulted with, companies that, even to this day, are considered conventional. What I remember most about him is his insistence that, when it comes to vineyards, Mother Nature has the final say on what grapes should be planted, how they are farmed, and the style of the resulting wines. Tchelistcheff believed that “man” has only so much control, and that what comes naturally should be respected.

These values were good enough for Tchelistcheff and they’re good enough for me.

Expert Editorial

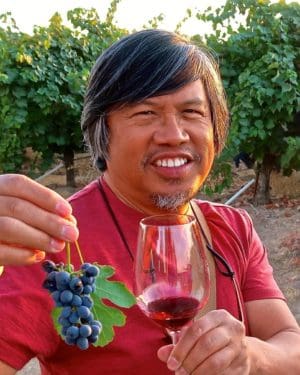

Randy Caparoso is a full-time wine journalist/photographer living in Lodi, California. In a prior incarnation, he was a multi-award winning restaurateur, starting as a sommelier in Honolulu (1978 through 1988), and then as Founding Partner/VP/Corporate Wine Director of the James Beard Award winning Roy’s family of restaurants (1988-2001), opening 28 locations from Hawaii to New York. While with Roy’s, he was named Santé’s first Wine & Spirits Professional of the Year (1998) and Restaurant Wine’s Wine Marketer of the Year (1992 and 1998). Between 2001 and 2006, he operated his own Caparoso Wines label as a wine producer. For over 20 years, he also bylined a biweekly wine column for his hometown newspaper, The Honolulu Advertiser (1981-2002). He currently puts bread (and wine) on the table as Editor-at-Large and the Bottom Line columnist for The SOMM Journal (founded in 2007 as Sommelier Journal), and freelance blogger and social media director for Lodi Winegrape Commission (lodiwine.com). You may contact him at randycaparoso@earthlink.net.