When it comes to wine choice, consumers have always been more sophisticated than industry professionals.

By Randy Caparoso

I started out on Burgundy but soon hit the harder stuff.

Not really. But I always loved that line from Bob Dylan’s song, “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues.”

As it were, after more than 45 years in the wine business, wines made from Pinot Noir, the black-skinned grape of Burgundy in France, remain some of my favorites. Why? Because Pinot Noir usually produces a soft, silky, fragrant, spiced red wine. I drink it when I’m feeling fancy or eating fancy (such as filet mignon or rack of lamb).

For everyday drinking, though, I prefer good ol’ California Zinfandel, which also tends to be soft, spicy and fragrant, only a little zestier than Pinot Noir-based reds. More like spaghetti wines — but who doesn’t love spaghetti? If Zinfandel also had caffeine and tasted good when hot, I’d probably drink it for breakfast with my cereal. I recently I enjoyed a Zinfandel with a spiced sausage ragú and soft polenta; the following night, the other half of that bottle of Zinfandel paired with a salad with crispy chopped chicken gizzards in a balsamic vinaigrette. Life is good when Zinfandel is in it.

True Burgundy comes from a specific region (of that name) in France. Back in 1981, when I penned my first-ever newspaper column for my hometown newspaper, The Honolulu Advertiser, the “Burgundy” most familiar to Americans was the cheap, easy and (at best) inoffensive red-colored wine bottled in inexpensive “jugs.” You could buy squat 1.5-liter bottles of “Burgundy” by brands such as E. & J. Gallo, Paul Masson, Inglenook or Almadén for as little as $2.99. To the eternal horror of the French, California-grown Burgundy never contained a drop of wine made from actual Pinot Noir, the required grape of France’s Burgundy.

Hi Bob

Many old-timers can still recall when Robert Mondavi “went back” to Lodi. Mr. Mondavi originally moved to Lodi with his family during the early 1920s, at the age of 9, and graduated from Lodi Union High School. His father, Cesare, made enough money in the Lodi grape packing industry to send all four of his kids to Stanford. The family later purchased a defunct winery in Napa Valley called Charles Krug, which Robert and his brother Peter resuscitated and operated together until the mid-’60s when Robert founded his seminal Robert Mondavi Winery.

While Mondavi’s eponymous Napa Valley brand swiftly took the wine world by storm for its premium quality varietals — such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Sauvignon Blanc (sold under the Frenchified name, Fumé Blanc), as well as Chardonnay and Pinot Noir — Mondavi himself always believed that California was capable of producing the world’s finest wines for everyday consumption, or what the French might call vin ordinaire. But he didn’t think it was possible to do it in Napa Valley.

Therefore, in 1979, Mondavi purchased the old Cherokee Vineyard Association cooperative winery east of Hwy. 99 in the little Lodi area hamlet of Acampo. He renamed the facility Woodbridge because it was located on Woodbridge Road (not actually in the community of Woodbridge, which is on the other side of the city of Lodi). Today, wines coming out of there are bottled under the Woodbridge by Robert Mondavi label.

Instead of generic wines such as Burgundy, Chablis, Sauterne, Chianti, etc., the very first Woodbridge Winery products were called, simply, “Robert Mondavi Table Red,” “Robert Mondavi Table White,” and “Robert Mondavi Table Rosé.” Locals called them “Bob Red,” “Bob White” and “Bob Rosé.”

Table wines

Those “Bob” wines of yore were blends of multiple grapes, just like the generic Burgundy and Chablis wines popular in the day. Mondavi, however, emphasized the fact that these were “table” wines because he wanted consumers to pick up on them as beverages meant for daily consumption, belonging on the table with food. He often talked of his dream of Americans adopting the gastronomic wine cultures of Europe, while obviously wanting to get away from borrowing European place names for wine labels.

Because he wanted to get away from the presumably less noble “jug wine” image, he packaged his “Bob” blends in cork-finished magnums, forcing countless Mondavi customers across the country to lower the top shelf of their refrigerators to accommodate the extra-tall bottles of white or rosé.

Mondavi and his team at Woodbridge also began exhorting the local growers in Lodi to plant the same grapes that were being successfully sold under the Robert Mondavi varietal labels sourced from Napa Valley: Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc and even Pinot Noir and Merlot (before Mondavi returned to Lodi, Merlot did not exist in Lodi vineyards — in fact, it was practically nonexistent in Napa Valley as well). As a sign of the times, the Napa Valley Robert Mondavi brand also produced a Chenin Blanc and Zinfandel (both varietals dropped by the winery by the mid-1990s).

Soon after, by the mid-1980s, many California wineries also began to successfully sell varietal wines such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay and (by the late 1980s) White Zinfandel for as little as $2.99 to $4.99 per 750mL bottle. Even though, at the time, varietal wines were associated with ultra-premium categories, they no longer needed to be priced that way. You can say that Mondavi’s dream of California producing the “finest everyday wine in the world” was coming to fruition. The cheap varietal bottlings of the ’80s were far more appealing than the generic Burgundy and Chablis wines of previous decades. And the industry’s lower priced iterations of popular varieties are even better today.

WWRMD

To my mind, Mondavi’s history — or at least his thought process — parallels the history of California wine in general, the same way Dylan gave shape, or intelligent voice, to rock and roll.

Maybe it’s because Mondavi is no longer around, but the American wine industry, in general, now seems to find itself in something of a collective befuddlement over how to get younger generations — consumers in their 20s and 30s — to purchase wine with as much commitment or gusto as previous generations. Especially as much as boomers, who, despite their creaky bones, continue to anchor the wine market in general. The problem, of course, is that boomers aren’t getting any younger. Who knows how long they can keep the wine wine industry afloat? Maybe the question should be: What would Robert Mondavi do?

I seriously doubt he’d be wringing his hands. We hear a lot, for instance, about the fact that today’s wines are expensive. Well, it’s true, many of these well-heeled boomers and Xers (the latter group, now in their 40s and 50s) are consuming $50, $100 and $200 wines like it’s nothing. Still, it’s also true that there are far more choices of wines priced between $5 and $15 than ever before. Certainly far, far more value-priced brands and bottlings than what boomers were offered 40 or 50 years ago.

The reality, it is clear, is not that wines are expensive, but that younger generations don’t have to drink wine at all. They have more choices. There are close to 20 or 30 times more brands of beer than there were 40 or 50 years ago. Younger consumers are also gobbling up hard seltzers, ciders, liquors and pre-mixed cocktails like there’s no tomorrow. When they were in their 20s, today’s boomers had meager choices between, maybe, Lancers, Mateus, Blue Nun, Budweiser or Miller Lite, or (if they really wanted to live it up) Robert Mondavi Fumé Blanc or Cabernet Sauvignon. Today’s younger generation is infinitely more spoiled when it comes to adult beverages.

But I’m not worried. Fine wine still has something none of the other alcoholic products have. It has more of a sense of artistry combined with a pervasive sense of nature, or what comes organically with Mother Nature’s blessings. Yes, you get the same alcoholic buzz when consuming wine, but the variations of finer wines are such that they also perk the mind, or stimulate the intellect or curiosity natural to us as thinking animals. We have the option of choosing to consume beverages for reasons beyond satiation or inebriation. Good wine does that in spades.

Art and science

Where nature comes in is the fact that the finest wines still vary from vintage to vintage simply because they are made from grapes, and grapes grow differently each year, producing variations as different as the places they’re grown, despite the efforts of the wine industry as a whole to homogenize them. The latter is never going to work because the product simply doesn’t lend itself to that.

That is to say: Vintners, working hand in hand with nature still have endless options on how to cultivate grapes and how to turn those grapes into wine. Perhaps the one thing Mondavi used to always say that I disagree with is that, “wine is a perfect combination of art and science.” Not really. The finest wines in the world all come from special places, regardless of the art and science going into them. Therefore, the finest wines end up having some kind of distinct sense of time and place — specific sensory qualities that reflect origins, the hands of time, the minds of people… art and science defined by nature.

Even in California, that dual epitome of farming and industrialization. Virtually all California wine, from the most commercialized to the most handcrafted and exalted, tends to be softer yet fresher and more fruit-forward than comparable wines grown in Europe, mostly because California is lousy with the Mediterranean climate conducive to that style of wine. A California Chardonnay may be fruitier than a Chardonnay from France’s Burgundy, and California Cabernet Sauvignons are invariably bolder and bigger than French counterparts in Bordeaux. All for good reason, which is not a choice thing. California wines possess exactly what the French have always referred to as terroir — their own “sense of place.” So there!

The beauty of the whole thing, of course, is that wine consumers have endless choices. If they prefer wines that are, generally speaking, less overtly fruity and more earthy or minerally, they’re not stuck with California wine. There are wines from seemingly every pocket of Europe that are as unfruity as they come. If they like red wine, it doesn’t have to be a big, bold Cabernet Sauvignon from Napa, Sonoma or Paso Robles. It can be a light and frisky Cinsaut from South Africa, a lean and lanky Chianti or Valpolicella from Italy, a leathery Cahors or scrawny Beaujolais from France. The list goes on and on and it’s all here, on practically every store shelf in America.

Knowing what’s “good”

I believe it was the legendary (even if nearly forgotten) British wine journalist named André Simon who once wrote that we can all have good taste, but not necessarily the same taste. Think of good wine as being like music or art — or food, since wine is similar to food in that it ends up going down the hatch. Not all of us like broccoli or Brussels sprouts, just like not all of us like White Zinfandel or red Zinfandel, Dolly or Dylan, Puccini or Pollock, Emily Brontë or Emily Dickenson.

I have always been amused, working in wine-related industries, by how much most professionals in the trade, wine production and media still act like babies. They still have to be told what’s “good,” and they rely so much on numerical ratings amounting to nothing more than opinionated data for some kind of confirmation. Yet all the while, for consumers themselves, choosing the “best” wines has always been pretty straightforward. Consumers end up choosing wines the same way they choose their books, their favorite dishes, the clothes they wear, the music they listen to, the movies they watch and anything else falling somewhere within the realm of art, craft or taste. They just know and, for the most part, they don’t need confirmation from anyone to decide.

Consumers, in that sense, have always been more sophisticated than industry professionals. I’m even ashamed of sommeliers (yes, I used to be one), who are among the worst followers of what other people tell them. The consumers themselves, as it turns out, are always the ones who drive the trends that wine professionals are endlessly chasing, the same way they drive fashions and production of any product on the market.

The mystery of wine

The taste of consumers, of course, is constantly evolving. The worse thing you can do is insult them by giving them the same ol’ stuff. Honestly, that’s not much of a mystery. Generally speaking, they just want better products, and they are willing to pay anything — very little, about the same or a lot more — to get what they want. Mondavi figured that out 50 years ago, simultaneously producing constantly improved wines for both cheaper and higher prices. He was called a genius for that self-evident observation.

Wine, in fact, may still be a “mystery” to most consumers. I take that as a positive — a help, not a hindrance. It is good, after all, to have sweet mystery in our lives. That’s what drives sales and marketing: things that prompt consumers to investigate further and discover to their great joy, surprise, illumination. Otherwise, everyday life would be pretty boring, wouldn’t it?

Ultimately, we all exercise our human faculty of making choices. To each his (or her) choice. As Dylan once put it, You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.

As for me, I’m going back to New York City, I do believe I’ve had enough.

I’m not exactly sure of what that means either, but that’s another Dylan line, applicable to any point in life or state of mind involving a decision or crossroad. No matter, it just sounds good — the ring of imaginatively composed music being as important to us as the feel of a well conceived wine, explicable or inexplicable, cryptic or explicit.

Life is too short, after all, for lousy wine. I’m not sure who first said that, or if I’m the first person to say something as obvious as that. Let’s just say, try not to overthink things. Just give the people what they want.

_________________________________________________________________

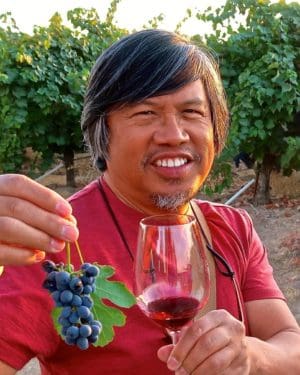

Randy Caparoso

Randy Caparoso is a full-time wine journalist/photographer living in Lodi, California. In a prior incarnation, he was a multi-award winning restaurateur, starting as a sommelier in Honolulu (1978 through 1988), and then as Founding Partner/VP/Corporate Wine Director of the James Beard Award winning Roy’s family of restaurants (1988-2001), opening 28 locations from Hawaii to New York. While with Roy’s, he was named Santé’s first Wine & Spirits Professional of the Year (1998) and Restaurant Wine’s Wine Marketer of the Year (1992 and 1998). Between 2001 and 2006, he operated his own Caparoso Wines label as a wine producer. For over 20 years, he also bylined a biweekly wine column for his hometown newspaper, The Honolulu Advertiser (1981-2002). He currently puts bread (and wine) on the table as Editor-at-Large and the Bottom Line columnist for The SOMM Journal (founded in 2007 as Sommelier Journal), and freelance blogger and social media director for Lodi Winegrape Commission (lodiwine.com). You may contact him at randycaparoso@earthlink.net