As temperatures creep up (or down),

winemakers make plans and prepare for what’s to come.

By Laura Ness

How is climate change impacting grape growing in the United States? It’s complicated. Some areas are getting warmer and finding it a boon, like Oregon, while others are finding they can’t make ice wine anymore and are also dealing with wildly unpredictable frosts, like New York.

Hotter and colder

Says Scott Osborne, co-owner of Fox Run Vineyards in Penn Yan, N.Y., “When I first came here, we never had to worry about late frost, since the water in Seneca Lake kept the nighttime temperatures cool enough to prevent bud break until after the last frost. Over the last 10 years, the winters have been so warm that the water in Seneca Lake is warmer, which has led to early bud break. Almost all varieties are threatened, but early bud break varieties like Pinot Noir and Chardonnay seem to be the most vulnerable to these late frosts.”

Dr. Tim Martinson, retired statewide director of Cornell Cooperative Extension in Ithaca, N.Y., says, “In general, more heat means a longer growing season, which is mostly favorable. Mid-winter risk of cold injury persists with spring frost due to early budburst and more extreme rain events.” Post-veraison, he expects that the warmer night temperatures and more saturated soil moisture in September will drive more disease pressure.

California has seen ripeness earlier and earlier over the past two decades, and extreme weather-fueled wildfires are causing grave concern. “Early on in the 1980s and ’90s, harvest time for Chardonnay was generally the last week of October or the first week of November. Now it’s the first half of October,” Silver Mountain Vineyards’ Jerold O’Brien tells us from the Santa Cruz Mountains. “Twenty years ago, we planted Pinot Noir on the coolest slopes we have. Now with global warming, it’s too warm for these grapes.” He’s actually planting more Bordeaux varieties.

Eric Wente, whose family has farmed in Livermore, Calif., for 140 years, and for the past 60 in Salinas, muses, “Is it global cooling or warming? The whole state did not have a problem ripening last summer [2022: which experienced extreme triple digit heat in September], but look at harvest dates: Livermore Cabernet is still being harvested long after Napa is done. I think we are in good shape, until the ocean warms up a lot.”

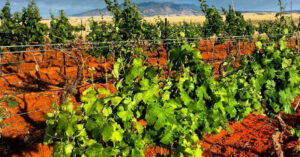

In Sonoita, Ariz., winter’s cold and late season frosts are peskier than heat. President of the Arizona Wine Growers Association and founder of Callaghan Vineyards, Kent Callaghan, assures us, “Other than 2020, which was hot as hell and another year we were wiped out by hail, we’re getting cooler and wetter. Odd but true.” Arizona is on track to have its third below average temperature growing season in a row. In 2019, Callaghan had frost on May 19. He says his most successful cultivars are Grenache, Marsanne and Clairette, which were part of an experimental planting of Rhônes, inspired by the visage of Randall Grahm on the cover of Wine Spectator, in Lone (Rhône) Ranger garb.

In Verde Valley, Ariz., Paula Woolsey and Michael Pierce, both of whom teach enology and viticulture at Yavapai College, shared, “While we face the challenges of spring frosts, summer heat, dry periods, etc., overall the biggest climate-related challenge is the erratic nature of the weather patterns. The climate is simply unstable.” Two seasons of hot and dry were followed by two seasons of monsoons, bringing unusual fungal pressure. The extremes are getting more extreme. “The cultivars most adversely impacted by climate change are early budding and tight-clustered grapes, such as Chardonnay, Petite Sirah, Sauvignon Blanc and Zinfandel.”

One of the most renowned experts on the impact of climate change on viticulture is Dr. Greg Jones, who now manages Abacela in Oregon’s Umpqua Valley. Overall, he says, climate change has benefitted Oregon for the last 60 years, with Pinot Noir and Chardonnay adapting nicely. But, he cautions: “How warm is too warm? Issues of heat stress are evident for both varieties as the state now sees more days over 90°F or 95°F than ever and even seeing very extreme heat such as in late June of 2021 Chardonnay evidence worldwide says it has more tolerance to higher temperatures than Pinot Noir, but with either, style differences are likely as the climate continues to warm.”

Evan Martin of Martin Woods & HiFi Wine Bar in McMinnville, Ore., notes, “Establishing new vineyards in the Willamette is getting harder to do without irrigation, which hasn’t been common in our local industry. Unusually dry springs over the last 10 years have caused widespread vine loss in new plantings without irrigation systems. In contrast, our well-established vines with deep root systems seemingly remain quite capable of handling our dry, hot summer season without irrigation.”

Rob Griffin, known as “The Dean of Washington Wine,” is celebrating the 40-year anniversary of his winery Barnard Griffin. “Grape maturity has advanced by weeks due to a generally warmer climate,” he says. “Anecdotally, my first Washington harvest in 1977 started in early October. Recent years have started in mid-August.”

There are upsides, too. In Oregon, they can plant at elevations not previously attempted. Says Tom Mortimer of Le Cadeau Vineyard in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, “When I planted our vineyard 25 years ago, I was told by growers [at that time] that the preferred elevation was 400 to 500 feet, and the preferred aspect was south-facing. Today, it’s not unusual to see Oregon vineyards planted at elevations up to 800 feet, sometimes higher, and in some cases, north facing slopes are planted.” Le Cadeau vineyard is in the 600 to 780 ft range, which Mortimer considers the sweet spot — for today.

“Perhaps the warmer South-facing slopes will lose favor to cooler North-facing locations,” says Griffin.

Replanting in response?

Growers are also shifting their varietal mix, in part due to market preference but also in response to climate vagaries.

Predicts Martin, “I think the Willamette Valley will remain the premier terroir in the United States for growing world class, cool-climate Chardonnay and Pinot Noir for many, many years to come. I’m not making any adjustments to the varietal mix in my portfolio, which also includes Gamay, Grüner Veltliner and Riesling [plus Cab Franc and Syrah from The Rocks District of Milton-Freewater AVA]. I’ve always been focused on late-ripening, high elevation sites in the cooler, naturally air-conditioned sector of the Willamette Valley.”

Abacela’s Jones notes, “The Willamette Valley has warmed to the point that some growers are experimenting with slightly warmer climate varieties such as Gamay, Merlot, Syrah and Tempranillo. But none of this is wholesale shifting. It’s more about trying to be aware of how these varieties can perform in the soils, landscapes and current climate.”

Cornell’s Martinson reminds us that, since 1880, Cornell has been breeding grapes. More than 40 varieties are planted in the Finger Lakes region. “I expect climate change to be favorable for late-ripening varieties, especially reds such as Cab Franc.”

Osborne at Fox Run says, “At this point I’m not planting any new varieties. I have Chardonnay, Riesling, Cabernet Franc and Lemberger planted. I don’t see the changes happening radically enough to warrant replanting or adding a new variety.”

Observes Griffin, “Late ripening varieties, such as Petit Verdot and Albariño, look promising in a warmer future for Washington. Market demand is still a bigger factor than climatic concerns in planting decisions.”

In Texas, Chris Brundett of William Chris Vineyards and Lost Draw Cellars notes, “Tannat continues to perform well. Mourvèdre, Picpoul, Roussanne, Cabernet, Cinsault and Sangiovese all seem to produce better and better in the hot climate. Montepluciano and Aglianico are really developing nicely. Tempranillo is still in that category.”

In Arizona, Woolsey and Pierce tell us, “Cultivars that like the warmth and retain acidity do well in the Verde Valley include Barbera, Aglianico, Malvasia Bianca and Viognier. Many of the Willcox growers have Spanish and Rhône varieties planted, including Grenache, Tempranillo and Mourvèdre. Sonoita vineyards [in Southern Arizona, 25 miles from the Mexican border] is more sensitive to spring frosts and leans towards late-budding varieties.”

Adapting in the vineyard

What’s happening faster than replanting are adjustments in the vineyards. Growers nationwide are increasingly adopting later pruning schedules to deal with late spring frosts, and many are adjusting irrigation, canopy management and rootstocks.

Washington’s Griffin says, “Extreme summer heat is causing us to rethink irrigation protocols [we’re watering more] and canopy requirements [also more]. The relative abundance of water is a regional asset. Forward-looking growers are including sprinkled water cooling capacity as a control option to excessive heat.

Brundett says that heat impacts stressed vineyards more, especially those under drought pressure. “We’re working on farming grapes with water strategies to retain acidity and build more mid-palate by using soil moisture sensors to dial in the irrigation tighter.”

According to Le Cadeau’s Mortimer, “Longer term, I suspect we’ll see warmer sites adjust their strategic inputs. But for now, short-term management adjustments are working fine in Oregon. Generally speaking, I don’t think that overall wine quality has ever been higher.”

Griffin observes, “Rootstock use is relatively new to Washington. Historically, pressure from extreme cold winter events resulted in growers choosing ‘own rooted’ vines to allow retraining of vines from underground wood — an impossible practice with rootstock. Washington was traditionally a poor habitat for Phylloxera, a major reason for adopting rootstock. Recently, though, Phylloxera has been identified in certain isolated locations, so clearly that genie is out of the bottle. Rootstock may prove useful in retarding grape ripening, a possible asset in a warmer climate.”

Martin says some recent plantings have been done of ungrafted, self-rooted vines in the Willamette Valley. “My instincts and observations tell me that self-rooted vines are inherently better at nutrient and moisture transfer from soil to vine. This gives them an advantage in non-irrigated vineyards in dry years. If we are in fact getting dryer, then perhaps this outweighs at least some of the risk of phylloxera.”

Counters Callaghan, “Ironically, we’re going back to the original rootstock that we planted on 5C (advances maturity). 1103P extends the season, which is a big problem here. We have monsoon moisture through about the middle of September. But then we see potential hurricane moisture arriving in early October.”

Are consumers ready for varieties they’re not familiar with? Yes, says Brundett, as long as the wines are well-made. “For years, I felt like the fat penguin on the edge of the iceberg — the one that all the other penguins pushed in the water to see if there were any sharks. That was us planting and working with lots of varieties. The market is responding by snagging up the best vintages and blends upon release.”

Another trend in response is to pick earlier. Says Mike Sinor, who farms the Bassi Vineyard in the tiny SLO (San Luis Obispo) Coast AVA of Calif., “We are so close to the ocean [1.2 mi], I don’t see a major shift in varieties. I think the more you go inland, the more you will see shifts. What has changed is canopy management. Very few spots are pulling leaves and exposing clusters as much as we did a few years ago. I also see brands just picking earlier to retain the acid. Customers now seem to be much more into lighter, low alcohol wines. Back in 2010-2011, the wines from these vintages were very low in alcohol, but the customer really wasn’t into those wines back then.”

Ultimately, customers will adapt, just like growers. What choice do we have?

___________________________________________________________

Laura Ness

Laura Ness is an avid wine journalist, storyteller and wine columnist (Edible:Monterey, Los Gatos Magazine, San Jose Mercury News, The Livermore Independent), and a long time contributor to Wine Industry Network. Known as “HerVineNess,” she judges wine competitions throughout California and has a corkscrew in every purse. However, she wishes that all wineries would adopt screwcaps!