Whether shipping wine across the globe in giant bladders, or biking a bottle down the street, there’s likely a way to make the trip cheaper for you and better for the environment.

—Kathleen Willcox

Two forces are causing the wine industry to transform the way it ships wine.

On the one hand, there’s the strangled global supply chain. Shipping routes have turned into constrictor knots (remember when the Suez Canal was blocked?), extreme weather has stymied ships, and ports and factories have shut down amid COVID-19 flare-ups and labor issues. The result is severe supply shortages affecting every industry, including wine, with makers finding it increasingly difficult to get basics like bottles and labels. The situation is so severe, the International Monetary Fund downgraded the U.S. growth forecast this month by one percentage point.

On the other hand, there’s the carbon footprint of transportation to take into account. While it would be difficult to estimate how much a wine bottle’s footprint has ballooned amid the logistical shipping chaos caused by the pandemic, even during normal times, about 68 percent of a wine’s carbon footprint comes from packaging and transportation, climate scientist Dr. Richard Smart has estimated.

Many winemakers and distributors have been trying to lower wine’s carbon footprint for years, but amid shortages, extreme weather, and ever-more dire predictions about climate change, many are tackling these issues with increasing urgency, in both large and small ways.

Global Moves

When Nicolas Quillé joined the Crimson Wine Group as COO four years ago, he quickly realized that transforming the way the group ships, organizes, and distributes goods is essential for economic and ecological reasons. With three wineries in California, one in Oregon, and two in Washington, resulting in about 350,000 cases of wine produced annually, there were a lot of initial elements to coordinate.

“I began to look at carbon emissions as a whole,” Quillé explains. “There are the goods coming in, and the finished goods going out. Two separate streams involving many indirect contributions.”

Simplifying and lightening the load was the first step. “Each winery had several different bottle shapes, about 30 total,” he says. “There were 13 warehouses with inventory everywhere, which created a lot of back-and-forth activity. We also began sourcing all of our packaging supplies from within North America to shorten the supply chain.”

Now, Crimson is down to five bottles shapes and three warehouses, and has become a member of third-party sustainability groups like the Porto Protocol and the International Wineries for Climate Change. In the past two years, Crimson has transitioned more than 90 percent of its glass to domestically produced lightweight bottle and reduced its carbon footprint by 300 tons of carbon annually.

“It’s about slowly peeling the onion,” Quillé says. “We even look at the ingredients in the glass, and make sure that silica is produced in North America, not shipped from overseas. The next step is exploring how to change the way the DtC market works.”

The DtC market exploded during the pandemic, he comments, but shipping one bottle to one consumer is extremely inefficient. “We want to see if we can ship 24 at once, and let them know how much that would save in terms of the carbon footprint,” Quille says. The strategy: make consumers partners in the sustainability effort by giving them the option to offset shipping at checkout.

Like the Crimson Group, Cono Sur Vineyards & Winery, in Colchagua Valley’s Chile, takes a bird’s eye view of the carbon footprint, aiming to cut back on the use of fuels and electricity by incorporating solar energy in vineyards and the warehouse, reducing the number of flights executives take, lowering wine bottle rates, and streamlining shipping. With 2 million cases produced annually, the impact of the reduction is significant.

“When Cono Sur’s internal carbon footprint work was being measures formally by the the Société Générale de Surveillance (SGS), under the Carbon Footprint Assessment protocol from Carboneutral, it showed that the C02 emitted for each ton of wine packaged and sold went down from 1.01 to 0.899 tons of C02 per ton of wine,” says senior brand manager Heather Jones.

Jones, like many other globally minded people in the wine industry, realizes that pausing global commerce isn’t possible. There are, as of yet, no widely available ways to eliminate carbon output.

Instead—and in order to be certified CarbonNeutral—Cono Sur annually offsets about 10,118 tons of carbon emissions generated by transportation, with a third-party certified West India Wind Power Project.

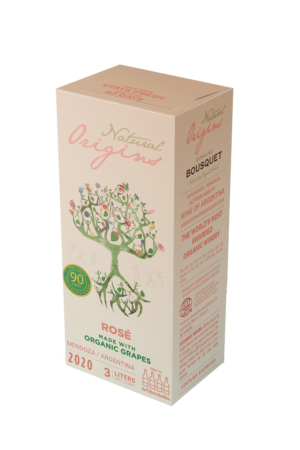

Other producers, like the Uco Valley’s Domaine Bousquet, which sells 250,000 cases annually in the U.S. alone, are reducing their carbon footprint and eliminating supply chain headaches by bottling some wines in the market where they will be sold.

“Bottling some of our entry-level wines on arrival in the marketplace rather than at the source in our winery is part of our drive toward integrated sustainability,” says Labid al Ameri, co-founder of Domaine Bousquet and president of the winery’s importing arm, Origins Organic Imports, based in Miami. “Since the bag-in-box category is price sensitive and the wines come with a limited shelf life, it makes sense.

They ship the wine in giant bladders, allowing them to send 6,300 gallons at once, instead of the 2,800 gallons they would have sent if in bottles or a box. This also allows Domaine Bousquet to pass along cost savings to the consumer. This year, about 180,000 cases of their Natural Origins bag-in-box wine will be filled domestically.

The initiative has been so successful, al Ameri says they will begin bottling some of their Domaine Bousquet Malbec and Cabernet Sauvignon, and their new line of canned wines, in California too.

Thinking Local

Meanwhile, one micro-distributor based in Eugene, Oregon, is taking the hyper-local view of carbon reduction and supply chain solutions.

“We’re a normal wine distributor, but we use a micro-warehousing model with the goal of lowering the carbon footprint of deliveries,” says Todd Eldman, Bitcork’s co-founder, explaining that they work with 23 wineries in Oregon, Washington and California, with two warehouses in Portland and one in Eugene. All of the warehouses are small and housed within existing office complexes, which means their additional heating and cooling requirements are “nil,” Eldmans says.

But delivery set-up is where Bitcork really stands out.

“We work with 125 restaurants in Oregon,” he says. “Many are within a few miles of our warehouses. The reality is, especially now, when restaurants are operating on such tight budgets, they can only order a few bottles or cases at a time. Instead of delivering them in a truck, we send them by bike messenger. If the order is too big for a bike, we work with a courier delivery service that has hybrid vehicles in its fleet.”

The pandemic-induced hospitality shut-down was tough for Bitcork, but they survived. Now, they’re looking to expand.

“We are looking at New York, DC, and Miami,” Eldman says. “For both the wineries and the restaurants, this model makes economic and ecological sense, saving on fuel, reducing carbon footprint, and enabling small orders as needed.”

_______________________________________________________________________

Kathleen Willcox writes about wine, food and culture from her home in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. She is keenly interested in sustainability issues, and the business of making ethical drinks and food. Her work appears regularly in Wine Searcher, Wine Enthusiast, Liquor.com and many other publications. Kathleen also co-authored a book called Hudson Valley Wine: A History of Taste & Terroir, which was published in 2017. Follow her wine explorations on Instagram at @kathleenwillcox